Making Mandalas

Each person's life is like a mandala – a vast limitless circle. We stand in the centre of our own circle, and everything we see, hear and think forms the mandala of our life.

Pema Chodron

‘In Sanskrit mandala means both circle and center, implying that it represents the both the visible world around us and the invisible one deep inside our minds and bodies… A mandala is a sacred space, often a circle, which reveals inner truth about you and the world around you.’ (Clare Goodwin, 1996)

I love to look at and create mandalas. A mandala is an intricate pattern radiating out from a central point.

It's an inherently calming and uplifting process: starting at the edge of a circle and gradually work inwards, bringing together separate elements into a harmonious whole. You can draw or paint a mandala – I find it particularly rewarding to work with natural materials, especially since so many plants and flowers naturally have mandalas within them.

I’ve taught my Multidimensional Mandala workshop several times now, and although we follow the same format each time, it's always a special and unique experience. I especially like teaching this workshop at festivals as bringing a group of individuals together to create something beautiful that is greater than the sum of its parts is a nice metaphor for the festival experience, and the form of the mandala itself. Sharing this workshop at our home studio, with our community and plants from our garden will be extra special!

Find out more about our celebrations and workshop here

Mandalas throughout history

The word 'mandala' comes from Sanskrit. Loosely translated it means circle, but a mandala is more than a shape, and of course goes by different names depending on the culture creating it. Intricate patterns within circles, created with ritual and intention have been used as tool for contemplation, meditation and healing for thousands of years across many cultures. A similarity which seems to apply across cultures is the both the creator and the viewer seem to benefit from the uplifting and harmonious effects of this process.

This list are just the examples I have discovered so far, and I am always open to learning more - please let me know if there are any that I have missed!

Buddhist Mandala Making

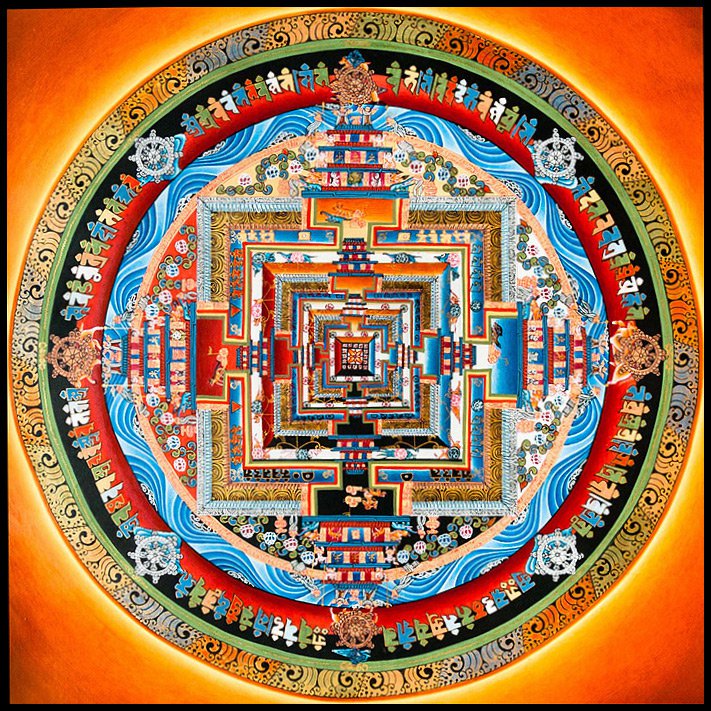

Above: Mandala of Kalachakra Wheel,

Some of the most well known mandalas come from Tibetan Buddhist tradition, with each phase, from building to viewing to dissolving being a different type of meditation.

There are hundreds of different sand mandala designs in the Tibetan tradition. Each represents a different tantric deity, and every precise detail reflects a different aspect of each deity, and of Buddhist philosophy. The physical act of creating the intricate mandala from crushed semiprecious stones is a meditation and an offering.

Within Vajrayana, the Tibetan tantric branch of Buddhism, some students create 100,000 mandalas as a preliminary practice before beginning the actual tantric teachings.

A mandala is said to bring peace and harmony to the area where it is constructed. Viewing a mandala is believed to “be enough to change one's mind stream by creating a strong imprint of the beauty of perfection of the Buddha's mind, as is represented in the mandala itself. As a result of this imprint, one may be able to find greater compassion, awareness, and a better sense of wellbeing.” (source: www.themandalaproject.org)

The dissolution of the mandala is also a meditation on non-attachment and the impermanence of all things.

Rangoli

Rangolis are a beautiful South Asian tradition which use chalk powder to create intricate patterns around the entrance of a home, especially at Diwali.

Above: a rangoli design for Diwali

‘This colourful tradition was initially started to commemorate the victory of good against evil. It is also associated with Goddess Lakshmi, who can bless you with wealth. As per Indian beliefs, a well-decorated entry with bright Rangolis is an inviting factor for good luck and prosperity…According to the Hindu Dharma, putting Rangoli on important days of the year is auspicious. Especially on Diwali, which marks the homecoming of Lord Rama after a victorious battle against Ravana, these patterns symbolize hope and happiness! In different parts of India, these art forms are known by other names like “Kolam”, “Muggulu”, “Kolangal”, “Alpana” etc.; Deepavali designs are largely focused on symmetry choice of colours and themes to bring in the festive spirits.

Mandalas in Islamic Art and Architecture

Above: The Tomb of Hafez in Iran

Mandalas also feature in Islamic art and architecture, from beautifully intricate tiles, to the designs of the structures themselves. Again, gazing at the pattern of the mandala can be used as a way in to meditation, contemplation and transcendence

‘The mandala is a symbol of existence and a system based on revelation. These decorations subconsciously draw attention for concentration during religious meditation that is considered to focus and

search within oneself.’ read more here

‘With its origins in Eastern religions of Hinduism, Buddhism and others, mandala art is a map of the universe. In addition to this, mandala art in Islam combines geometric arrangements and cultural motifs symbolising their connections with Allah (God). The mosque grounds include mandalas, similarly to Eastern religions, the circle represents Allah and everything within it represents His beauty, His creations and the infinite nature of the universe.

Navajo Sandpainting Traditions

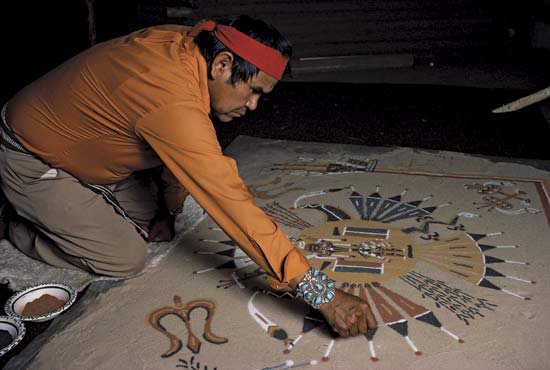

Above: Sandpainting in action

The Navajo people created vast sand mandalas and medicine wheels with rituals that lasted up to nine days.

‘According to Navajo belief, a sandpainting heals because the ritual image attracts and exalts the Holy People; serves as a pathway for the mutual exchange of illness and the healing power of the Holy People; identifies the patient with the Holy People it depicts; and creates a ritual reality in which the patient and the supernatural dramatically interact, reestablishing the patient's correct relationship with the world of the Holy People ( GriffinPierce 1992:43). For the Navajo, the sandpainting is a dynamic, living, sacred entity that enables the patient to transform his or her mental and physical state by focusing on the powerful mythic symbols that re-create the chantway odyssey of the storys protagonist, causing those events to live again in the present. The performative power of sandpainting creation and ritual use reestablish the proper, orderly placement of the forces of life, thus restoring correct relations between the patient and those forces upon which the patient's spiritual and physical health depend. The sandpainting works its healing power by reestablishing the patient's sense of connectedness to all of life ( Griffin-Pierce 1991:66).’

Learn more about Navajo traditions here

Christian Traditions and Gothic Architecture

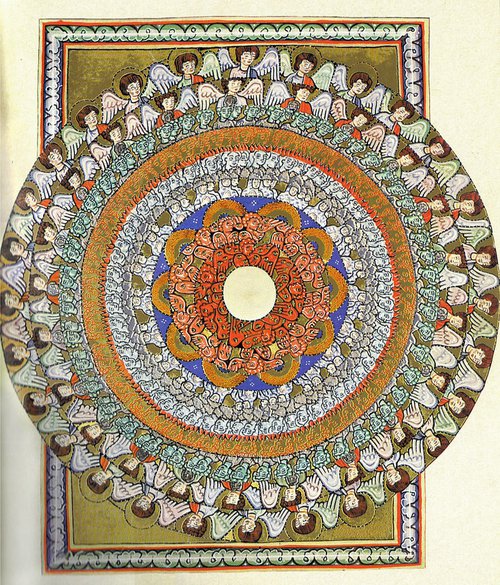

Above: The Choirs of Angels. From the Rupertsberg manuscript.

Hildegard Von Bingen was a twelfth century Christian nun used them to illustrate her own visions and beliefs.

Hildegard was a German Benedictine abbess and polymath active as a writer, composer, philosopher, mystic, visionary, and as a medical writer and practitioner during the Middle Ages. She is also one of the best-known composers of sacred monophony music, and is considered by scholars to be the founder of scientific natural history in Germany.

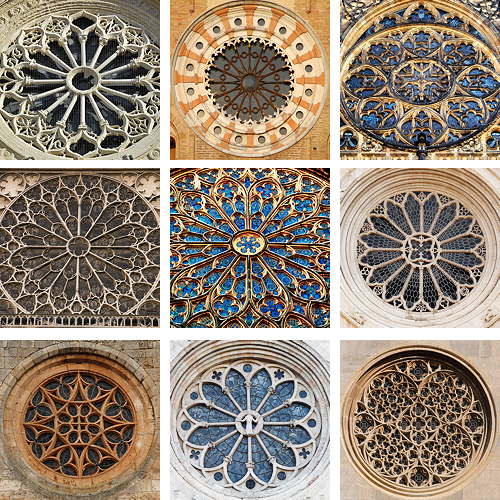

We also see mandala like forms emerge in Gothic cathedrals in the form the rose window (below).

Mandalas in psychology

Carl Jung (1875- 19610, a Swiss psychiatrist and psychoanalyst and influential figure in literature, philosophy and religious studies, used mandalas in his art making practice to explore the unconscious. He found that the circle motif appeared in his own exploration and that of his patients.

"I sketched every morning in a notebook a small circular drawing...which seemed to correspond to my inner situation at the time....Only gradually did I discover what the mandala really is:...the Self, the wholeness of the personality, which if all goes well is harmonious." (source: Carl Jung, Memories, Dreams, Reflections)

Psychologist and meditator, David Fontana, explains that the symbolic nature of the mandala can help “to access progressively deeper levels of the unconscious, ultimately assisting the meditator to experience a mystical sense of oneness with the ultimate unity from which the cosmos in all its manifold forms arises.” (source: David Fontana, Meditating with Mandalas)

Contemporary mandala makers

Above: A Kathy Klein Danmala

Kathy Klein, a devotional artist, was a big inspiration for my own mandala making process. She creates 'danmalas': dan meaning: the giver; mala: garland of flowers. Klein begins by centring herself in a meditative devotional state of mind and collects her flowers and natural elements while in this state. She then continues her meditation as she arranges these elements and leaves them as a gift for whoever might find them (they are often built in urban locations).

“They are reflections of the inexpressible, a gesture which points towards life's abundance, an unspoken verse of Love. The danmalas remind us all to listen to the unheard voice of nature, creation and the eternal mystery.” (source: www.danmala.com)

The Human Mandala Project brings people together and explores collaborative yogic postures as art. The project uses sacred geometry and the intention of the group as a healing process, for themselves as individuals and also to send positive energy to their location.

“By creating these forms with our human bodies, we draw upon the resonant peace that emits from our planet and is meant for healing all beings.” (source: www.humanmandala.com/manifesto)

Sacred Geometry and Mandalas in Nature

Above: A natural mandala in our garden!

Maybe one of the reasons that mandala like shapes hold significance in many different cultures, is that we see them throughout nature in so many ways. Once you start noticing them you will see more and more - some of my favourites are the shapes you see within succulent plants.

"Natural patterns are all around us. Look into the center of a sunflower. A snowflake. You are observing, feeling, or responding to repeating vibrations and patterns of energy.” (Emma Mildon 2021)

As Jemma Foster adds, the living spiral of a nautilus shell or the horn of a sheep, the interlocking hexagons of a beehive, the underground formation of crystals, the spin of a spider's web, and the formations of migrating birds—these are all designs and patterns that are so much more than an aesthetic.

"Their beauty is functional," she notes. "Their structure creates the specific dynamic, strength, and balance required to support the role of the individual and collective.” (Foster 2021)

Mandalas at Garden of Yoga

I’ve been inspired by rituals of these wonderful traditions, and the natural mandalas created by Mother Nature and have used these symbols in my own art, which is created in a contemporary urban setting. I personally find the mandala making process to be centering and uplifting, and a way into creative flow and meditation. I choose to make my mandalas like nature, embracing the slight variations along the way rather than trying to force a ‘perfect’ form.

This approach intersects well with the process of stencil art, where you can use a set form to create increasingly intricate layers of pattern and colour over time, but using the medium of spray paint means that there is always an element of chance in the mix!

They are created on industrial glass light covers - a gift from our friends at ecovantage, passed on to us since this type of glass is not recyclable.

My Mandalas are listed in our online store, but they are pick up only (I'm scared to post the glass!).

While our studio was being built I loved the idea of embedding a symbol of harmony and community - these is a hidden mandala stencilled under our floor boards directly below the nature mandala we will be building in our workshop.

Garden of Yoga Mandala Workshop

The workshop runs from 3-4pm. We create the mandala, in a sensory friendly environment with soft light, no music and a table and chairs to make the building process more accessible.

We will start at the edge of the mandala and work inwards, following the circles of the mat base. Please be aware that if many people want to help build the mandala we might each build a small amount.

This is a contemplative and collaborative process, and we’ll keep any talk quiet and focused. The emphasis is on the process, not the end product, which we will all put our energy into and on the process of creation as meditation. You are also welcome to watch, which can be a meditation in itself.

We will use plants from our garden here, as well as the pebbles and glass that I’ve used in my festival mandalas.

In our practice we gradually work towards a deeper state of meditation. We use the mandala as a dristi – a means of centering ourselves mentally within the practice, and shared creative process. Just as when we build the mandala, we start with the gross – the outer layer – and work towards the more subtle inner layers. We conclude the practice with a guided meditation and relaxation around the mandala.